Myanmar faces a critical moment for investment decision-making. The Barack Obama administration’s move to lift sanctions on the Southeast Asian country has opened up new opportunities. But the moves that are made today will send political and economic ripples into the future, and the international community must act responsibly.

China wants to finance a 3,600-megawatt hydropower dam called Myitsone — one of the largest in Southeast Asia — with the goal of directing most of the power back to China. This project, however, could compromise peace negotiations between rebel forces in the northern state of Kachin and the Myanmar government.

Construction of the dam stalled in 2011 and presents a critical test for Aung San Suu Kyi’s governing National League for Democracy party.

Villagers in Kachin have expressed extreme opposition to the megaproject, which raises severe environmental concerns and threatens livelihoods. The issue is particularly complex due to geopolitical factors: lucrative financing from China, pressure to improve human rights from the U.S. and international community, and free trade deals with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Proceeding with the dam would diminish the authority of Myanmar to stand up to China and would exacerbate ethnic tensions that already run high between local communities and the national Myanmar government. Past promises from Chinese companies to share the benefits of hydropower development have only displaced villagers and destroyed local livelihoods in Myanmar. This case is no different. A resolute stance against Myitsone could empower local communities — and such empowerment remains critical to developing peace and stability.

Engagement with key stakeholders is necessary for a sustainable and peaceful 21st-century power system that works for the people.

National electrification

Currently, hydropower planning is a source of conflict, with local villagers excluded from the decision-making process. With the right approach, though, this could become an opportunity to build peace and supply sustainable energy to local communities.

First, a sincere and open dialogue that engages key local stakeholders is necessary for reconciliation and building trust. Secondly, thorough environmental impact assessments with the involvement of local stakeholders would go a long way to improving transparency. Finally, the international community has the power and responsibility to support Myanmar with technical assistance and state-of-the-art science, encouraging bottom-up, small-scale hydropower and distributed renewable energy development.

Electricity access initiatives led by multilateral development banks call for an aggressive push toward 100% electrification by 2030. Currently, only around 35% of Myanmar has access to power, which in many cases does not meet the needs of citizens. The 100% target could be achieved in a cost-effective manner with local resources, including the solar- and small-hydro-based mini-grids that are rapidly emerging across the country.

“Free” has a price

For the past three years, in collaboration with Chulalongkorn University, we have held a series of stakeholder meetings in Bangkok with current and potential investors regarding the prospects for independent power producers, or IPPs, throughout Myanmar. These workshops have shed light on the IPP predicament facing the country and its neighbors. The “free power and free share” model — under which Myanmar is entitled to free electricity and stakes in such projects — fails to deliver prosperity, as fair mechanisms for allocating the benefits are not institutionalized. Often, local communities do not receive electricity and lose out on alternative investments in energy resources that require less transmission and distribution infrastructure.

Banks play a key role in driving such agreements. Until now, IPPs have tried to maximize exports to neighboring countries and minimize financial risk in emerging markets like Myanmar. The lack of credibility among Myanmar’s power utilities enables neighboring countries to take advantage of lax regulations and opportunities for lucrative investment at the expense of local villagers. As the Myanmar government often cannot grant concessions to cross-border IPPs due to a high risk of credit default, the benefits remain unrealized in many cases.

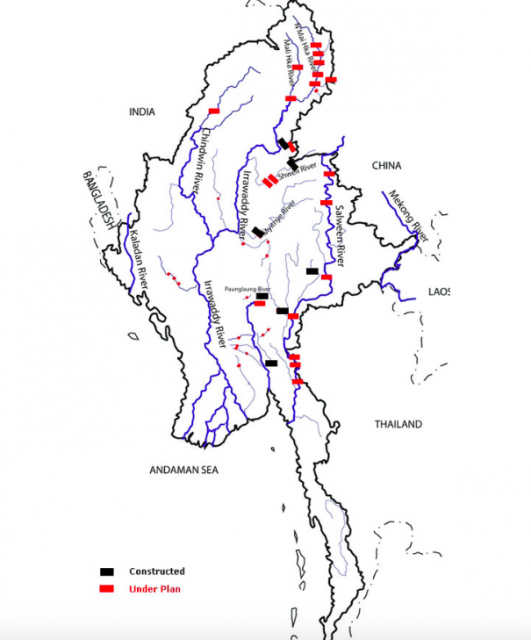

Most of the hydropower development proposals in the Salween river basin during the last decade have not been built. A few large-scale cross-border IPPs currently operate in tributaries of the Irrawaddy River, including Shweli1, which has installed capacity of 600MW, and Dapein1, which has 240MW. While the electricity generated there is mainly exported to China, the IPP agreement grants 10–15% of total project generation and shareholdings for free to Myanmar.

The conventional wisdom is that “free power, free share” remains a prerequisite for concessions by Myanmar. But this concept is inherently flawed.

For example, our field survey in Shweli1 makes it clear that 15% of generated power is provided for free to the state-owned mining company and military camp, while neighboring towns must purchase electricity at 4–8 cents per kilowatt-hour and villages must re-import electricity from China at 20 cents per kilowatt-hour. These tariffs are higher than tariffs on the grid.

To make things worse, the “free” benefits in Myanmar fuel conflict by compounding inequality among civilian groups. One example of this is the Mong Ton dam in Shan State, promoted by the previous military government. Nongovernmental conservation groups held an anti-dam campaign “to urge the government as well as Chinese and Thai investors to immediately stop plans to build dams, as this is causing conflict and directly undermining the peace process,” as Burma Rivers Network put it. Salween Watch, a civil society watchdog, sees the construction of dams as “one of the strategies used by the military regime to gain foreign support and funding for its ongoing war effort” while viewing dams as “a strategy to increase and maintain its control over areas of ethnic land after many decades of brutal conflict.”

With the democratically elected NLD government having taken power in 2015, Myanmar has an opportunity to escape past nightmares and begin to distribute benefits equitably. Certainly, monetary compensation and free power seems appealing to local communities in need of electrification and economic development. However, as the NLD rightly states, it is much more critical to secure livelihoods and the environment by pursuing sustainable development practices.

Villagers depend on income from natural resources, including forest and fisheries products. Our field survey regarding the Mong Ton hydropower development shows that local villagers cite deforestation, river flows and flood damage as their top dam-related concerns. Investigations into the effects of dam construction are critical undertakings that must become part of the hydropower decision-making and planning process. Without them, there can be no trust, and a strong local backlash against the influential, military-tied Ministry of Interior is inevitable.

Start with science

In the past, Myanmar’s government glorified dams while environmental groups vilified them. Neither stance was grounded in rigorous scientific evaluations, and each side’s argument fed the other’s distrust — creating resentment and hampering dialogue.

To move forward, we recommend establishing regulations on environmental impact assessments that include public disclosures. Building reliable institutions to enforce such rules poses a challenge, but doing so could help to bridge the gap between groups and restore trust — something that has been lost in Kachin and Shan states since 2011, as recent flare-ups in violence demonstrate.

The timing is urgent. The peace process remains on the cusp of an agreement. Rural electrification efforts are underway, but we know that distributed mini-grids from local solar and hydropower resources can be built and deployed faster than megaprojects, supporting peace efforts. The opportunity cost of inaction is high. Continuing the Myitsone project as a concession to China, meanwhile, could undo half a decade of peace negotiations and further damage the environment while negatively impacting villagers and their livelihoods.

In short, increased transparency and local engagement could usher Myanmar toward peace and prosperity. At the same time, it is up to the international community to expand the country’s intellectual and institutional capacity. We can support Myanmar’s infrastructure development not only through hard and soft loans, but also with technical assistance.

Myanmar needs environment- and people-friendly hydropower planning. Only then will the projects support peace-building rather than conflict.

Noah Kittner is an NSF graduate research fellow and doctoral student in the Energy and Resources Group at the University of California, Berkeley. Kensuke Yamaguchi is a project assistant professor at the University of Tokyo Policy Alternatives Research Institute. This was developed in conjunction with the Program on Conflict, Climate Change, and Green Development in the Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory.

For the article link in Nikkei Asia Review, click here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.