NEWS A Fruitvale Microgrid Could Inspire Resiliency if Approved

A Fruitvale Microgrid Could Inspire Resiliency — if Approved

![]() A Contributor from our Next-Gen Inspiration Team

A Contributor from our Next-Gen Inspiration Team

For the original, click here.

Two dozen homes in Oakland’s Fruitvale neighborhood are banding together to give their block a first-of-its-kind sustainability makeover. The EcoBlock, a UC Berkeley research project collaborating with the community, aims to affordably retrofit urban neighborhoods to have smaller carbon footprints and more reliable energy.

During its seven years in the making, the EcoBlock project has pushed through skyrocketing costs, permitting red tape, and compromises with Pacific Gas and Electric. Although researchers anticipated bringing upgrades to residents’ homes this spring, the lingering effects of the pandemic on supply chains and costs are still holding the project back. “Between COVID and inflation, our budget was just walloped,” says Therese Peffer, the principal investigator on the EcoBlock research team.

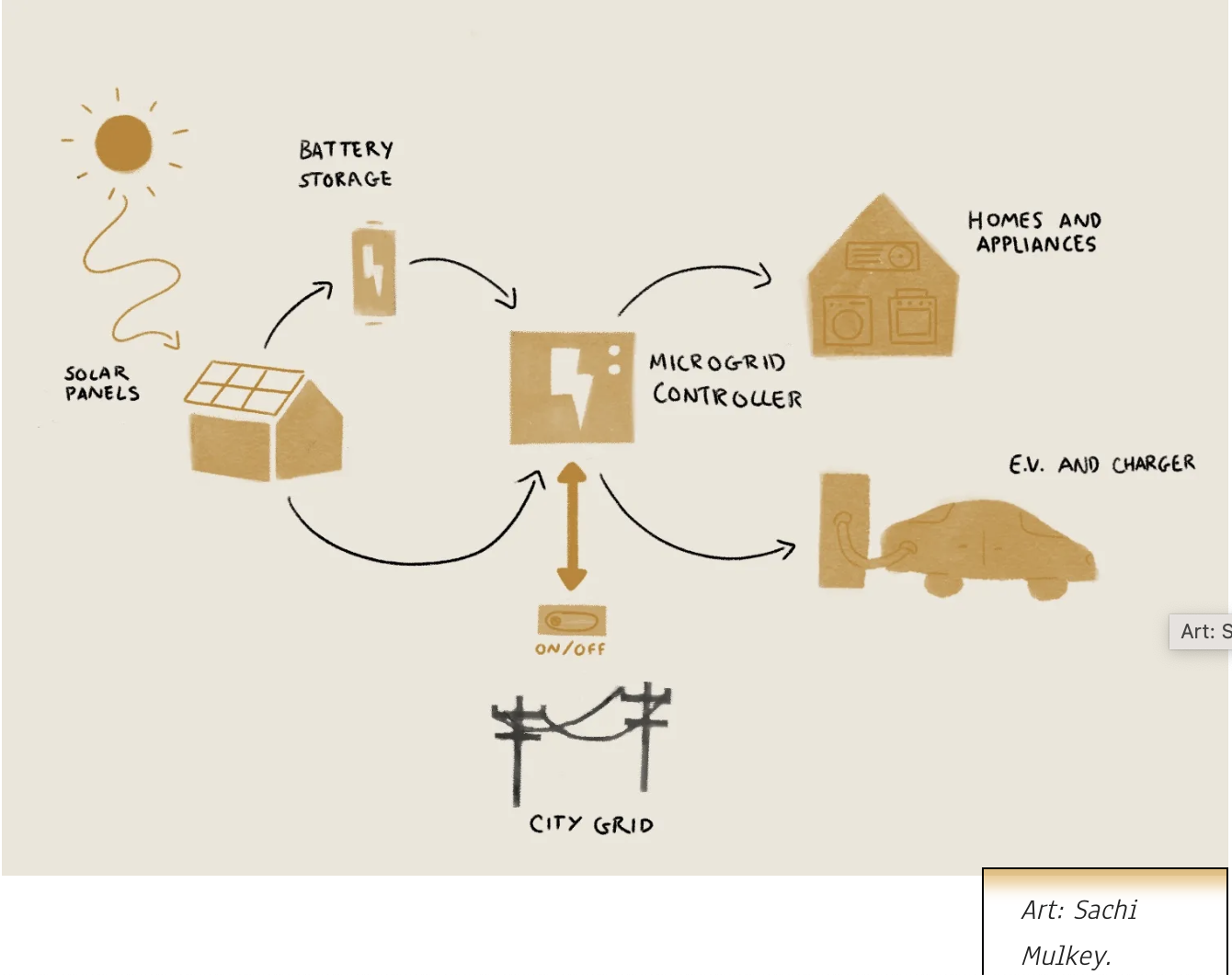

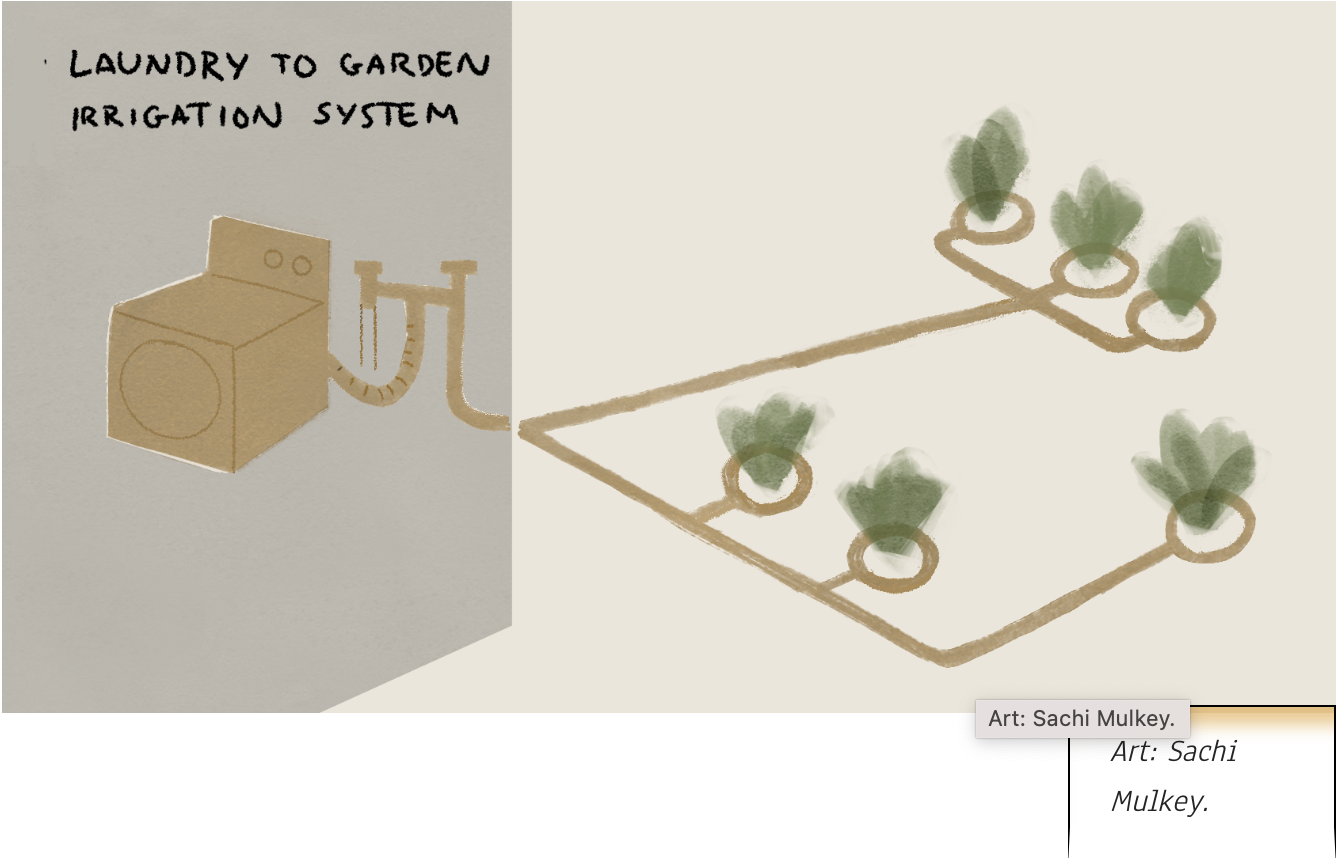

If the project is eventually implemented, the 25 Fruitvale homes participating in the EcoBlock can look forward to improved air quality, lowered water usage, and greener energy with new efficient electric appliances, air ventilation, water-recycling laundry, and a shared electric vehicle. The EcoBlock centers around a key piece of infrastructure: a small, localized energy system known as a microgrid.

By connecting to solar energy, a microgrid could provide the neighbors with electricity during blackouts or PG&E’s public safety power shut-offs during extreme weather events. And it’s been proven to work: In 2022, a microgrid community in Florida kept the lights on even as millions of homes lost power during Hurricane Ian.

The Fruitvale location was chosen out of a pool of self-nominated blocks by the UC Berkeley Research team, PG&E, and the City of Oakland based on vulnerability, levels of pollution, and the block’s position on the city’s electrical grid.

Daniel Hamilton, the Sustainability and Resilience Director for the city of Oakland, says that choosing a less wealthy area of Oakland was a priority. “There’s huge potential to help the frontline communities that are already suffering the effects of climate change and have fewer resources to do the work,” he says.

Also critical to the success of the project, say Hamilton and researchers, are the interest and collaboration of residents. In 2019, with the support of People Power Solar Cooperative, neighborhoods in Oakland were invited to apply to be the EcoBlock. “The Fruitvale site was the one where the community was most organized and already most supportive” but still vulnerable to climate impacts, says Hamilton.

Community liaison Cathy Leonard, a long-time Oakland native, says that the Oakland EcoBlock serves as a microcosm for the rest of the city. Residents range in age from 1 to 80 years old, speak four different languages, and are of “all different races and ethnicities for a truly diverse block.” For the project, Leonard has organized block parties and information sessions for the Fruitvale neighbors.

“In order for society to really address climate change,” says Leonard, “we have to worry about the homes that are already here.”

Since the project’s launch in 2015, the UC Berkeley research team has had to overcome a series of hurdles. The first site chosen failed due to neighborly disagreements. Then, while working on the Oakland neighborhood, the national cost of construction skyrocketed. In 2020, the pandemic came, bringing with it inflation and supply chain issues. Some parts of the EcoBlock, such as a residential charging station for the neighborhood’s shared electric vehicle, are a first for the city of Oakland and a streamlined permitting process has not yet been established. Other regulations, such as state-wide building codes, turn over regularly before the project can begin construction.

Although permits have been applied for, the project is in limbo while they are being processed. “I think the community members rightfully expected this to move much faster,” says Hamilton, noting the complexity behind EcoBlock, which has over a dozen partners and intersects with different regulatory bodies.

Among the red tape, the EcoBlock has had to contend with permitting and regulations by PG&E, which has a monopoly on utility management in the Bay Area. “I would say every step forward has been a battle against the inertia of slow-moving utilities,” says Dr. Daniel Kammen, the co-principal investigator for the EcoBlock.

Energy researchers say that while microgrids are a promising solution to an unreliable United States energy system, they are still uncommon. “Utilities are in no rush to promote clean energy that’s distributed, and not in their control,” says Kammen. ”Which certainly might be an outcome of a world full of microgrids.”

Originally, the researchers envisioned giving the residents a master meter, allowing them to “island” the block’s microgrid from the city’s grid, for truly self-managed solar energy. “PG&E did not like that,” says Peffer. Instead, each home is now planned to be equipped with its own solar meter, that feeds into the city’s energy supply as well as the EcoBlock microgrid.

PG&E has two programs for defraying the costs of microgrids. The Community Microgrid Enablement Program provides up to $3 million towards PG&E‑related costs of installing a microgrid. A forthcoming Microgrid Incentive Program has $200 million of funding from the California Public Utilities Commission and is anticipated to be launched jointly by PG&E and other regional utilities across the state in early 2023.

Paul Doherty, a spokesperson for PG&E, says that the EcoBlock is not eligible for this second program as it is not, “‘vulnerable to outages’ by our definition, not in a high fire-threat area, and not in our worst performing circuits list.” According to PG&E, out of the three dozen communities currently applying for microgrids, only one — The Redwood Coast Airport — has received funding through their incentive programs.

With the help of the Tuttle Law Group hired by the UC Berkeley researchers, the EcoBlock residents have formed a democratic community association through which they will co-own their microgrid, which includes a solar-power battery storage system.

This agreement gives the UC Berkeley researchers a 5‑year runway to study the success of the project and provides clear guidance on what happens if a property changes hands during that time. The EcoBlock research team will track the resiliency of the microgrid to blackouts — which can be triggered by extreme heat, rain, or cold — to inform energy policy in California.

In terms of adaptation, “two extremes exist today,” says Kammen. “We do good green things one home at a time, or we attempt too much at once.” With just one block, the EcoBlock team strives for an achievable example of upgrading our cities to be greener, kinder places to live.

You must be logged in to post a comment.