For the original in The New Yorker (February 19, 2021), click here.

By Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow

In 2004, Heather Hoff was working at a clothing store and living with her husband in San Luis Obispo, a small, laid-back city in the Central Coast region of California. A few years earlier, she had earned a B.S. in materials engineering from the nearby California Polytechnic State University. But she’d so far found work only in a series of eclectic entry-level positions—shovelling grapes at a winery, assembling rectal thermometers for cows. She was twenty-four years old and eager to start a career.

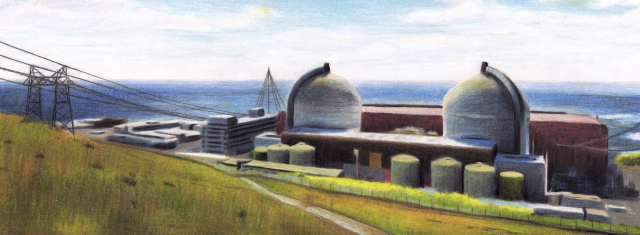

One of the county’s major employers was the Diablo Canyon Power Plant, situated on the coastline outside the city. Jobs there were stable and well-paying. But Diablo Canyon is a nuclear facility—it consists of two reactors, each contained inside a giant concrete dome—and Hoff, like many people, was suspicious of nuclear power. Her mother had been pregnant with her in March, 1979, when the meltdown at a nuclear plant on Three Mile Island, in Pennsylvania, transfixed the nation. Hoff grew up in Arizona, in an unconventional family that lived in a trailer with a composting toilet. She considered herself an environmentalist, and took it for granted that environmentalism and nuclear power were at odds.

Nonetheless, Hoff decided to give Diablo Canyon a try. She was hired as a plant operator. The work took her on daily rounds of the facility, checking equipment performance—oil flows, temperatures, vibrations—and hunting for signs of malfunction. Still skeptical, she asked constant questions about the safety of the technology. “When four-thirty on Friday came, my co-workers were, like, ‘Shut up, Heather, we want to go home,’ ” she recalled. “When I finally asked enough questions to understand the details, it wasn’t that scary.”

In the course of years, Hoff grew increasingly comfortable at the plant. She switched roles, working in the control room and then as a procedure writer, and got to know the workforce—mostly older, avuncular men. She began to believe that nuclear power was a safe, potent source of clean energy with numerous advantages over other sources. For instance, nuclear reactors generate huge amounts of energy on a small footprint: Diablo Canyon, which accounts for roughly nine per cent of the electricity produced in California, occupies fewer than six hundred acres. It can generate energy at all hours and, unlike solar and wind power, does not depend on particular weather conditions to operate. Hoff was especially struck by the fact that nuclear-power generation does not emit carbon dioxide or the other air pollutants associated with fossil fuels. Eventually, she began to think that fears of nuclear energy were not just misguided but dangerous. Her job no longer seemed to be in tension with her environmentalist views. Instead, it felt like an expression of her deepest values.

In late 2015, Hoff and her colleagues began to hear reports that worried them. P.G. & E., the utility that owns Diablo Canyon, was in the process of applying to renew its operating licenses—which expire in the mid-twenty-twenties—with the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Because its cooling system takes in and spits out about 2.5 billion gallons of ocean water each day, the plant also needs a lease from the California State Lands Commission in order to operate, and P.G. & E. was applying to renew that as well. Environmental groups had come to the commission with long-standing concerns about the effects of the cooling system on marine life and about the plant’s proximity to several geologic faults. The commission, chaired by Gavin Newsom, then the lieutenant governor, had agreed to take those issues into account. At a meeting that December, Newsom said, “I just don’t see that this plant is going to survive beyond ’24–2025.”

Around this time, Hoff discovered a Web site called Save Diablo Canyon. The site had been launched by a man named Michael Shellenberger, who ran an organization called Environmental Progress, in the Bay Area. Shellenberger was a controversial figure, known for his pugilistic defense of nuclear power and his acerbic criticism of mainstream environmentalists. Hoff had seen “Pandora’s Promise,” a 2013 documentary about nuclear power, in which Shellenberger had been featured. She e‑mailed him to ask about getting involved, and he offered to give a talk to plant employees. Hoff publicized the event among her colleagues, and baked about two hundred chocolate-chip cookies for the audience.

On the evening of February 16, 2016, a couple hundred people filed into a conference room at a local Courtyard Marriott hotel. Shellenberger told the audience that Diablo Canyon was essential to meeting California’s climate goals, and that it could operate safely for at least another twenty years. He said that it was at risk of being closed for political reasons, and urged the workers to organize to save their plant, for the sake of their jobs and the planet.

Kristin Zaitz, one of Hoff’s co-workers, was also in attendance. A California native and civil engineer, she had worked at Diablo Canyon since 2001, first conducting structural analyses—including some meant to fortify the plant against earthquakes—and then managing projects. Zaitz, too, came from a background that predisposed her to distrust nuclear power—in her case, an environmentally minded family and a left-leaning social circle. When she first contemplated working at Diablo Canyon, she imagined the rat-infested Springfield Nuclear Power Plant on “The Simpsons,” where green liquid oozes out of tanks. Eventually, like Hoff, she changed her thinking. “What we were doing actually aligned with my environmental values,” she told me. “That was shocking to me.”

Zaitz and Hoff sometimes bumped into each other at state parks, where both volunteered on weekends with their children. After Shellenberger’s talk, they lingered, folding up chairs and talking. Before long, they decided to team up. Using the name of Shellenberger’s site Save Diablo Canyon, they organized a series of meetings at a local pipe-fitters’ union hall. They served pizza for dozens of employees and their family members, who wrote letters to the State Lands Commission and other California officials. Other nuclear plants across the country were also at risk of closing, and soon they decided that their mission was bigger than rescuing their own plant. They wanted to correct what they saw as false impressions about nuclear power—impressions that they had once had themselves—and to try to shift public opinion. They would show that “it’s O.K. to be in favor of nuclear,” Zaitz said—that, in fact, if you’re an environmentalist, “you should be out there rooting for it.”

Hoff and Zaitz formed a nonprofit. Like the leaders of many other movements led by women—protests against war, drunk driving, and, of course, nuclear power—they sought to capitalize on their status as mothers. They toyed with a few generic names—Mothers for Climate, Mothers for Sustainability—because they worried that the word “nuclear” would scare some people off. But they ultimately discarded those more innocuous options. “We wanted to be really clear that we think nuclear needs to be part of the solution,” Zaitz said. They now run a small activist organization, Mothers for Nuclear, which argues that nuclear power is an indispensable tool in the quest for a decarbonized society.

On December 8, 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower delivered his “Atoms for Peace” speech at the United Nations General Assembly. He described the dangers of atomic weapons, but also declared that “this greatest of destructive forces can be developed into a great boon, for the benefit of all mankind.” Eisenhower proposed that governments make contributions from their stockpiles of uranium and fissionable materials to an international atomic-energy agency. One purpose of such an agency, he suggested, would be “to provide abundant electrical energy in the power-starved areas of the world.”

The first commercial nuclear power plant in the United States opened four years later, in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. In the following decades, dozens more were constructed. There are currently fifty-six nuclear power plants operating in the U.S. They provide the country with roughly twenty per cent of its electricity supply— more than half of its low-carbon electricity.

The plants were not always presumed to be environmentally unfriendly. At the dawn of the nuclear age, some conservationists, including David Brower, the longtime leader of the Sierra Club, supported nuclear power because it seemed preferable to hydroelectric dams, the construction of which destroyed scenery and wildlife by flooding valleys and other ecosystems. But Brower changed his mind in the late nineteen-sixties and, after a bitter split within the Sierra Club over whether to support the construction of Diablo Canyon, left to found Friends of the Earth, which was vehemently anti-nuclear. As John Wills explains in his 2006 book, “Conservation Fallout,” these disputes coincided with broader philosophical shifts. Conservationism—with its focus on the preservation of charismatic scenery for outdoor adventures—was giving way to the modern environmentalist movement, sparked in part by Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, “Silent Spring.” Carson’s book, which investigated the dangers posed by pesticides, articulated an ecological vision of nature in which everything was connected in a delicate web of life. Nuclear power was associated with radiation, which, like pesticides, could threaten that web.

By 1979, the U.S. had seventy-two commercial reactors. That year proved pivotal in the shaping of public opinion toward nuclear power in America. On March 16th, “The China Syndrome,” starring Jane Fonda, Jack Lemmon, and Michael Douglas, was released; the film portrayed corruption and a meltdown at a fictional nuclear plant. Twelve days later, one of the two reactors at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in southeastern Pennsylvania partially melted down. Most epidemiological studies would eventually determine that the accident had no detectable health consequences. But at the time there was no way the public could know this, and the incident added momentum to the anti-nuclear movement. By the time of the Chernobyl catastrophe, in Soviet Ukraine, in 1986—widely considered to be the worst nuclear disaster in history—opposition to nuclear power was widespread. Between 1979 and 1988, sixty-seven planned nuclear-power projects were cancelled. In the mid-eighties, the Department of Energy began research into the “integral fast reactor”—an innovative system designed to be safer and more advanced. In 1994, the Clinton Administration shut the project down.

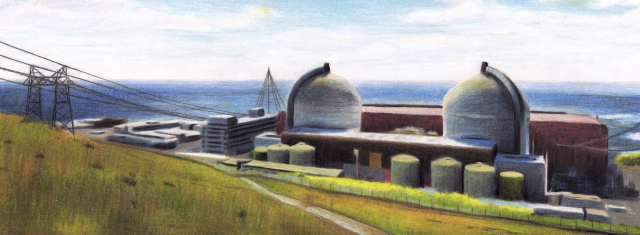

Today, the looming disruptions of climate change have altered the risk calculus around nuclear energy. James Hansen, the nasascientist credited with first bringing global warming to public attention, in 1988, has long advocated a vast expansion of nuclear power to replace fossil fuels. Even some environmental groups that have reservations about nuclear energy, such as the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Environmental Defense Fund, have recognized that abruptly closing existing reactors would lead to a spike in emissions. But U.S. plants are aging and grappling with a variety of challenges. In recent years, their economic viability has been threatened by cheap, fracked natural gas. Safety regulations introduced after the meltdowns at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, in 2011, have increased costs, and, in states such as California, legislation prioritizes renewables (the costs of which have also fallen steeply). Since 2013, eleven American reactors have been retired; the lost electricity has largely been replaced through the burning of fossil fuels. At least eight more closures, including Diablo Canyon’s, are planned. In a 2018 report, the Union of Concerned Scientists concluded that “closing the at-risk plants early could result in a cumulative 4 to 6 percent increase in US power sector carbon emissions by 2035.”

The past decade has seen the rise of a contingent of strongly pro-nuclear environmentalists. In 2007, Shellenberger and his colleague Ted Nordhaus co-founded the Breakthrough Institute, a Bay Area think tank known for its heterodox, “ecomodernist” approach to environmental problems. The organization, which presents itself as more pragmatic than the mainstream environmental movement, supports nuclear power alongside G.M.O.s and agricultural intensification. Other pro-nuclear groups include Third Way, a center-left think tank, and Good Energy Collective, a policy-research organization. (Shellenberger left the Breakthrough Institute, in 2015, and founded Environmental Progress, partly to focus more on efforts to save existing plants.)

The 2011 Fukushima disaster shifted the landscape of opinion, but not in entirely predictable ways. Immediately after Fukushima, anti-nuclear sentiment surged; Japan began to shutter its nuclear plants, as did Germany. And yet, as Carolyn Kormann has written, studies have found few health risks connected to radiation exposure in Japan in the wake of the accident. (The evacuation itself was associated with more than a thousand deaths, as well as a great deal of economic disruption.) Pro-nuclear advocates now point out that, after retiring some of their nuclear plants, Japan and Germany have become increasingly reliant on coal.

Heather Hoff watched news footage of the Fukushima disaster while at Diablo Canyon. What she saw resembled the scenarios she had learned about in training—situations that she had prepared for but never expected to face. “My heart instantly filled with fear,” she later wrote, on the Mothers for Nuclear Web site. For a time, her confidence in nuclear power was shaken. But, as more information emerged, she came to believe that the accident was not as cataclysmic as it had initially appeared to be. Eventually, Hoff concluded that the incident was an opportunity to learn how to improve nuclear power, not a reason to give up on it. She and Zaitz visited the site in 2018. They saw black plastic bags of contaminated soil heaped on the roadside, and ate the local fish. Afterward, they both blogged about the experience. Zaitz wrote that she understood the fear provoked by radiation, “with its deep roots in the horrendous human impacts caused by the atomic bomb.”

Pro-nuclear environmentalists often tell a conversion story, describing the moment when they began to see nuclear power not as something that could destroy the world but as something that could save it. They argue that much of what we think we know about nuclear energy is wrong. Instead of being the most dangerous energy source, it is one of the safest, linked with far fewer deaths per terawatt-hour than all fossil fuels. We perceive nuclear waste as uniquely hazardous, but, while waste from oil, natural gas, and coal is spewed into the atmosphere as greenhouse gases and as other forms of pollution, spent nuclear-fuel rods, which are solid, are contained in concrete casks or cooling pools, where they are monitored and prevented from causing harm. (The question of long-term storage remains fraught.) Most nuclear enthusiasts believe that renewables have a role to play in the energy system of the future. But they are skeptical of the premise that renewables alone can reliably power modern societies. And—in contrast to an environmental movement that has historically advocated the reduction of energy demand—pro-nuclear groups tend to focus more on the value that abundant nuclear energy could have around the world.

Charlyne Smith, a twenty-five-year-old Ph.D. candidate in nuclear engineering at the University of Florida, who shared her story on the Mothers for Nuclear Web site, grew up in rural Jamaica, where she had firsthand experience of “energy poverty.” During hurricanes, she told me, no one knew when the electricity would come back; food would spoil in the fridge. Smith learned about nuclear power as an undergraduate and decided to enter the field, with the goal of bringing reactors to the Caribbean. She is not naïve about the risks: she is writing a dissertation on nuclear proliferation. But, she says, “Waste and radiation—those are risks that are minimizable. Proliferation of nuclear material—that risk is minimizable. Versus what you can get out of nuclear energy, weighing the pros and cons. I strongly believe that nuclear energy can solve countless problems.”

The pro-nuclear community is small and fractious. There are debates about how large a role renewables should play and about whether to focus on preserving existing plants or developing advanced reactors, which have the potential to shut down automatically in the event of overheating and to run on spent fuel. (These reactors are still in the experimental phase.) There are also differences in rhetoric. At one end of the spectrum is Shellenberger, who seems to see mainstream environmentalists as his main adversaries; his newest book is titled “Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All.” His recent commentary decrying what he calls the climate scare has been widely circulated in right-wing circles and has perplexed some pro-nuclear allies. At the other end is Good Energy Collective, co-founded, recently, by Jessica Lovering, Shellenberger’s former colleague at the Breakthrough Institute. Her organization situates itself specifically on the progressive left, and is attempting to ally itself with the broader environmental movement and with activists focussed on social and racial justice. Mothers for Nuclear falls somewhere in between: their tone is less combative than Shellenberger’s, but Hoff and Zaitz often seem frustrated with anti-nuclear arguments and, in their social media feeds, point out the downsides of renewables—an emphasis that may turn off some of the people they are trying to persuade. (They believe that nuclear power should do most of the work of decarbonization, supplemented by renewables.)

Nuclear energy scrambles our usual tribal allegiances. In Congress, Democratic Senators Cory Booker and Sheldon Whitehouse have co-sponsored a bill with Republican Senators John Barrasso and Mike Crapo that would invest in advanced nuclear technology and provide support for existing plants that are at risk of closure; a climate platform drafted by John Kerry and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez included a plan to “create cost-effective pathways” for developing innovative reactors. And yet some environmental organizations, including Greenpeace and Climate Justice Alliance, deplore nuclear energy as unsafe and expensive. Perhaps most telling is the ambivalence that some groups express. Although the Union of Concerned Scientists has warned about the climate impacts of shutting down nuclear facilities, it has historically sounded the alarm about nuclear risk. Ed Lyman, its director of nuclear-power safety, told me that, because “there are so many uncertainties associated with nuclear safety analysis,” it’s “very hard to make a conclusion about whether it’s safe or not.” He noted, dispiritingly, that climate change could increase the hazards at nuclear plants, which will have to contend with more extreme weather events.

When Hoff and Zaitz officially launched Mothers for Nuclear, on Earth Day, 2016, they had to figure out how to tell their story and to change minds. The standard images of renewables—gleaming solar panels, elegant wind turbines in green fields—are welcoming, even glamorous. It seemed to Hoff and Zaitz that, by comparison, the nuclear industry had done a terrible job at public relations. By emphasizing safety, they thought, the industry had activated fears. Airlines don’t advertise by touting their safety records. It might be better to unapologetically celebrate nuclear energy for its strengths.

They gave talks at schools and conferences, shared stories on their Web site, posted on social media, and eventually started chapters in other countries. Iida Ruishalme, a Finnish cell biologist who lives in Switzerland and now serves as Mothers for Nuclear’s director of European operations, told me that she was drawn to the organization, in part, because of its appeal to emotion. The widespread impression, she said, is that “people who like nuclear are old white dudes who like it because it’s technically cool.” Mothers for Nuclear offered “this very emotional, very caring point of view,” she said. “The motivation comes from wanting to make it better for our children.” Ruishalme said that online commenters often tell her that the group is “clearly propaganda, a lobbyist front, not sincere—because it’s so preposterous to think that mothers would actually do this.” On the organization’s Web site, a photo montage of women and children is accompanied by a caption clarifying that they are pictures of real people who support the group—not stock images.

Among opponents, there is a long-standing assumption that anyone who promotes nuclear power must be a shill. The name “Mothers for Nuclear” sounds so much like something dreamed up by industry executives that it can elicit suspicion, even anger, in those who are anti-nuclear. The organization is entirely volunteer-run, with a tiny budget, and has not accepted donations from companies. But Hoff and Zaitz work at a nuclear plant and have been flown to give talks at industry-sponsored events; Mothers for Nuclear has received small donations from others who work in the industry. There is no denying the conflict of interest posed by their employment; even within the pro-nuclear community, their industry ties provoke uneasiness. Nordhaus, the executive director of the Breakthrough Institute, wrote in an e‑mail that, although he thinks Hoff and Zaitz are “well-intentioned,” nuclear advocacy should be independent of what he called “the legacy industry.” (The Breakthrough Institute has a policy against accepting money from energy interests.) Yet, from another angle, their connection to industry may be an asset. “Where they’ve been successful is coming at it from a personal perspective,” Jessica Lovering, the co-founder of Good Energy Collective, told me. Their approach to telling their stories, as outdoorsy, hippie moms, “humanizes the industry,” she said.

On a drizzly morning in May, 2019, when such visits were possible, Hoff and Zaitz offered me a tour of their plant. Hoff picked me up from my hotel in San Luis Obispo in her slate-gray electric Ford Focus, adorned with a “Split Don’t Emit” bumper sticker. While we waited for Zaitz at a café a few blocks away, Hoff told me about the lavender pendant hanging around her neck. Crafted for her by an artist she knew in Arizona, it was made partly of uranium glass, an old-fashioned material that has a touch of uranium added in for aesthetic purposes. “I wear it as a demonstration—radiation is not necessarily dangerous,” she said. Like many nuclear advocates, Hoff believes that the fears provoked by radiation are often unfounded or based on information that is not contextualized. A CT scan of the abdomen involves about ten times as much radiation exposure as the average nuclear worker gets in a year. Some scientists argue that no level of radiation exposure is safe, but others doubt that exposure below a certain threshold causes harm, and note that we are all exposed to natural “background” radiation in daily life. (Uranium glass emits a near-negligible amount.) Hoff and Zaitz believe that panic about radiation from nuclear energy has, cumulatively, caused more harm than the radiation itself.

After Zaitz arrived, we set out for Diablo Canyon. I rode up front; Zaitz sat in the back, pumping breast milk for her year-old daughter. The light rain had stopped, but mist still hung in the air. We passed through the town of Avila Beach, driving alongside the ocean. To our left, aquamarine water sparkled. On our right lay gently sloping terrain of grasses, sagebrush, wildflowers, and shrubs. The facility sits amid twelve thousand acres of otherwise unoccupied seaside land. Along the curving road, a sign proclaimed “Safety Is No Accident.” In the distance, the two massive containment domes rose above a cluster of shorter structures.

We pulled into the parking lot. In one of the outbuildings, I handed over my passport, then placed my jacket and bag in a plastic bin for an X‑ray. I walked through a metal detector, then stood under the arch of a “puffer machine,” which blasted me with air, shaking loose particles and analyzing them for traces of explosives. Once I’d been cleared, we walked upstairs to Hoff’s office, where the two women exchanged greetings with a few co-workers. We put on safety glasses and hard hats before entering “the bridge,” a narrow corridor with large windows that connects the administration building to the turbine hall. Through the windows, we could see the ocean, where water was continually cycling into and out of the plant. A security guard, armed with a handgun and a rifle, and wearing a red backpack, sauntered by.

The turbine hall, a vast space with a soaring, arched ceiling, was dominated by two large generators. Outside, within the two containment domes, uranium atoms were splitting apart in a chain reaction, heating water to more than six hundred degrees Fahrenheit; the steam spun the turbines, which in turn drove the generators. The resulting electricity would bring power to about three million Californians. Warm air rushed noisily around us. Through the din, Hoff explained different parts of the system: the pipes, the springs that supported them, the condenser, which takes wet vapor from the turbine exhaust and turns it back into liquid. Vending machines selling Pepsi and Chex Mix stood against one wall. I wasn’t allowed to take photos, but Hoff snapped a few of me and Zaitz. We smiled as if we were at Disneyland.

In June, 2016, not long after the formation of Mothers for Nuclear, P.G. & E. announced that it would not renew its operating licenses: the reactors at Diablo Canyon would cease operations in 2024 and 2025, respectively. The company said that its decision was based largely on economic considerations. Customer demand was declining, in part because of the growing popularity of a system called community-choice aggregation, in which localities can choose their energy sources; often they choose wind or solar farms (though they still need to rely on natural gas at night, when solar is unavailable). The year before, California had passed Senate Bill 350, which requires the state to derive half of its energy from renewable sources by 2030; since P.G. & E. would be legally required to increase its procurement of renewable energy, it could end up with more electricity than it needed if it kept Diablo Canyon online.

The environmental groups that supported P.G. & E.’s plan, including the Natural Resources Defense Council and Friends of the Earth, see it as a model for gradually transitioning to a grid fed entirely by renewable energy. P.G. & E. has pledged to replace Diablo Canyon with other low-carbon energy sources. And yet energy storage remains a major challenge. Even if P.G. & E. does manage to fill the gap without help from natural gas—a heavy lift—some argue that, given California’s ambitious climate goals, the state should be adding to its total portfolio of low-carbon energy rather than subtracting from it. Experts differ on the wisdom of the choice. Steven Chu, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who served as President Barack Obama’s Secretary of Energy, told me that he had urged P.G. & E. not to decommission the plant. “It’s really the last twenty to thirty per cent of electricity where it’s going to be hard to go a hundred per cent renewable,” he said. Daniel Kammen, a physicist and a professor of nuclear energy at the University of California, Berkeley, however, was more sanguine. Although he is not opposed to nuclear power, or even to keeping Diablo Canyon open, he said, “We don’t need nuclear, and we certainly can get to a zero-carbon future without nuclear. The mixture of other renewables means you don’t have to go there.”

Hoff and Zaitz are not especially optimistic about the future of Diablo Canyon, but they hope that, between now and the planned closure, P.G. & E. and state officials can be persuaded to reverse course. They seek to recruit ordinary Californians to their cause. After touring the plant, I accompanied them to a radio studio, where they were scheduled to be guests on Dave Congalton Hometown Radio, a popular local talk show. On the air, Hoff explained who they were. “Mothers for Nuclear offers a different voice,” she said. “Nuclear power plants are run by lots of men, and women have been more scared of nuclear energy. We’re here to offer the motherly side of nuclear—nuclear for the future, for our children, for the planet.”

The phone lines lit up. The first couple of calls were favorable. “It’s kind of nice to hear a little bit of sanity about nuclear power, for a change,” a caller named John said. But then Pete, a listener who said that he had protested the construction of Diablo Canyon back in the early eighties, brought up nuclear waste. “There’s been numerous efforts to put it here, put it there, put it in barrels, bury it in the sea, bury it in deep caves—this, that, the other thing,” he said. “I don’t think any really good solution has even come up.”

“Pete, where do you put your garbage?” Hoff asked. “Where do you put your plastic waste?”

“That’s not radioactive!”

“It’s still really damaging to the environment,” Hoff said.

“An accident at a nuclear plant is a lot worse than an explosion at an oil plant,” Pete said.

Zaitz jumped in. “The surprising thing, Pete, that we found out is that nuclear is actually the safest way to make reliable electricity when you look at even the consequences of the worst accidents we’ve ever had,” she said. “Any other energy source ends up, in the long run, killing more people, whether it’s due to air pollution, whether it’s due to industrial accidents. Air pollution kills about eight million people per year.”

As the conversation continued, Hoff and Zaitz held their own, but it seemed unlikely that many minds would be changed decisively. In trying to plan a carbon-free future, we are faced with imperfect choices and innumerable unknowns. In such situations, we typically go with our guts. Gut feelings are hard to alter. And yet, especially for younger people, nuclear power may not elicit visceral fears. Many people who did not grow up with the threat of a nuclear holocaust now face a future of climate chaos. Many lie awake at night imagining not meltdowns but lethal heat waves and calving glaciers; they dread life on an inexorably less hospitable planet.

Since I first met with Hoff and Zaitz, the coronavirus pandemic has upended the world. At Diablo Canyon, the comparatively small fraction of the plant’s workers who need to be on site—security guards, control-room operators, and the like—are now doing so in masks, and with other safety protocols in place; Hoff and Zaitz have been working from home. Meanwhile, last summer, wildfires set the West Coast ablaze. For Hoff and Zaitz, both crises have reinforced their existing beliefs. Evidence that air pollution exacerbates vulnerability to covid-19 is yet another reason to move away from fossil fuels; the importance of ventilators and other devices at hospitals underscores the need for reliable, around-the-clock electricity. Last August, when thick smoke blocked the sun in parts of California, solar output in those areas temporarily plummeted.

Rolling blackouts have raised questions about how California’s grid will function after Diablo Canyon is shut down. In May, the office of the California Independent System Operator, which is responsible for maintaining the grid’s reliability, filed comments to the state’s Public Utilities Commission. Its modelling, the office reported, showed that “incremental resource needs may be much greater than originally anticipated and that the system hits a critical inflection point after Diablo Canyon retires.” At the same time, the plant’s outsized role is not without drawbacks. The reactors periodically need to be taken offline for maintenance, withdrawing a substantial amount of electricity from the grid.

Our energy system is in flux. There are innovations under way in the renewables sphere—advances in battery storage, demand management, and regional integration—which should help overcome the challenges of intermittency. Nuclear scientists, for their part, are working on smaller, more nimble nuclear reactors. There are complex economic considerations, which are inseparable from policy—for example, nuclear power would immediately become more competitive if we had a carbon tax. And there are huge risks no matter what we do.

To be fervently pro-nuclear, in the manner of Hoff and Zaitz, is to see in the peaceful splitting of the atom something almost miraculous. It is to see an energy source that has been steadily providing low-carbon electricity for decades—doing vastly more good than harm, saving vastly more lives than it has taken—but which has received little credit and instead been maligned. It is to believe that the most significant problem with nuclear power, by far, is public perception. Like the anti-nuclear world view—and perhaps partly in response to it—the pro-nuclear world view can edge toward dogmatism. Hoff and Zaitz certainly seem readier to tout studies that confirm their views, and reluctant to acknowledge any flaws that nuclear energy may have. Still, even if one does not embrace nuclear power to the same extent, one can recognize its past contributions and question the wisdom of counting it out in the future.

One of the last times I spoke with Zaitz, she noted that a lot of people seemed to be feeling discouraged at this moment, overwhelmed by the scale of the challenges ahead. But she counselled against despair. “The hopeful way to go into that is, ‘Oh, wow, we actually have technology that can do this,’ ” she said. “And that’s nuclear. And so I’d rather stay hopeful.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.